A school day is built on small, stubborn acts of hope: a principal who refuses to lower the bar, teachers who keep showing up, learners who arrive carrying more than backpacks, carrying hunger, worry, and the quiet arithmetic of whether there will be food today.

In South Africa, hunger is not just a household problem. It becomes a classroom problem. And then, very quickly, it becomes an education outcomes problem.

That is why school feeding matters, as infrastructure for learning.

South Africa’s National School Nutrition Programme (NSNP) reaches millions of learners and is widely recognised as supporting attendance, concentration and cognitive function, the basic conditions that make learning possible. But the need remains deep. Nationally, food insecurity and hunger still show up in the data and the provincial picture is uneven.

One recent South Africa–focused analysis (SERI Report published 2025, using national household survey data) estimates about 22.2% of people were food insecure, with severe food insecurity highest in some provinces (including a higher estimate reported for the Western Cape than Gauteng in that analysis).

Then there is malnutrition — the slower, more invisible emergency.

Chwebeni Village,Eastern Cape. SA Harvest helping vulnerable people by delivering nutritious food to organisations across South Africa that feed those in need.

Chwebeni Village,Eastern Cape. SA Harvest helping vulnerable people by delivering nutritious food to organisations across South Africa that feed those in need.

15 March 2024 (photo Deon Ferreira)

Stunting (a marker of chronic undernutrition that can affect development and learning potential) also varies by province. In a 2024 UNICEF situation analysis summary drawing on the South African Early Childhood Review, provincial stunting prevalence is shown to differ sharply, with figures around the mid-teens in Gauteng, and higher levels indicated for provinces including KwaZulu-Natal and the Western Cape in that source.

All of this lands in one place: the learner. And that is where SA Harvest’s work intersects with education, not by “doing education,” but by protecting the conditions education requires.

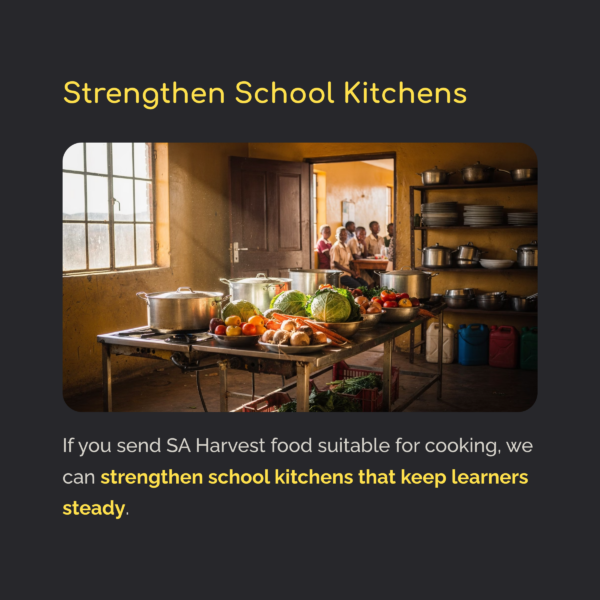

The school kitchen as a lever for change

Not every school has a functional kitchen. Not every school has consistent inputs. And not every community can absorb the volatility of food prices, unemployment, and household strain.

So when SA Harvest supports education organisations, we are not handing out random parcels and hoping for the best. We are strengthening a system: getting food to places that can cook, serve, and sustain learners through routine.

Because routine is everything when you’re building learning.

A meal at school doesn’t just fill a stomach. It buys back attention. It reduces the noise of hunger. It gives teachers a class that can stay present for longer than the first period. It gives learners a body that can carry a brain through algebra, reading, and the long concentration of becoming.

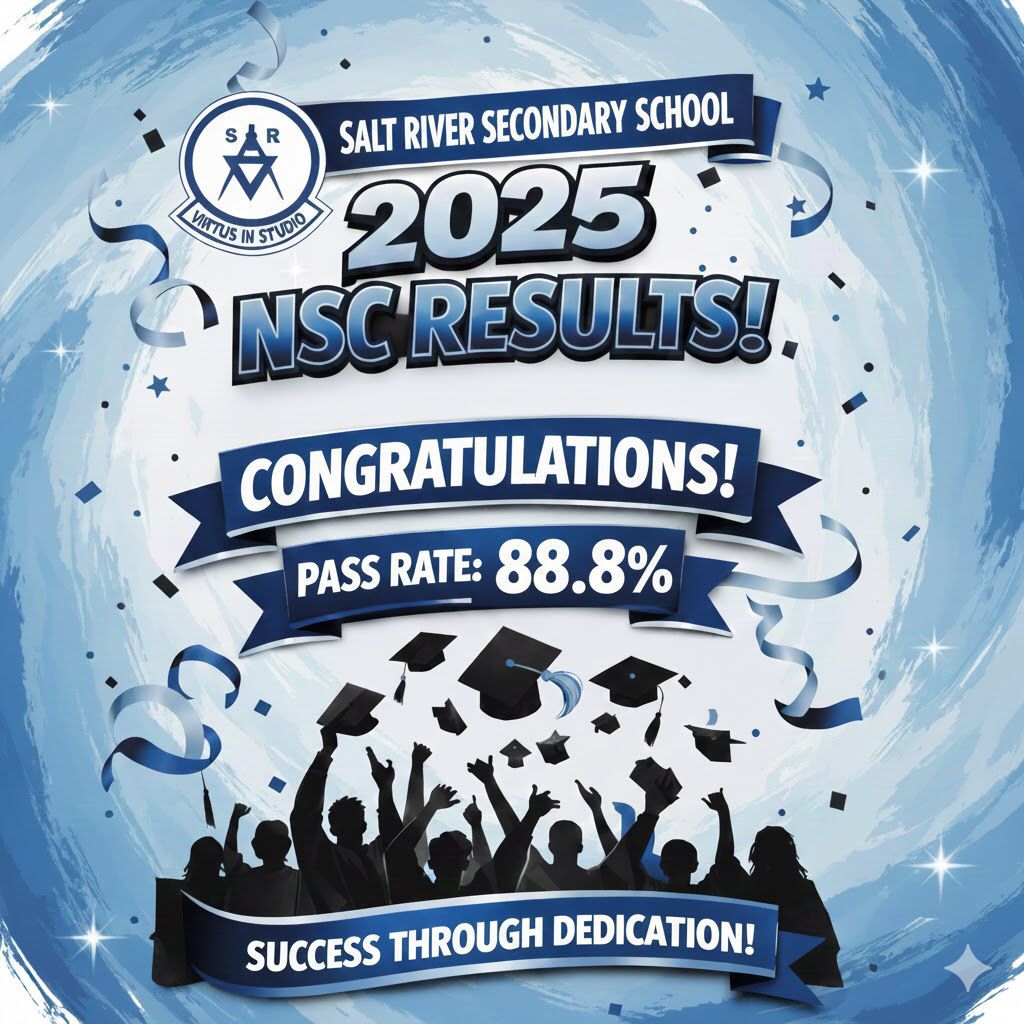

Salt River High: the proof-point

Sometimes, impact arrives as a graph so steep it stops you in your tracks.

Salt River High shared their rates for matriculant passes from when they started collaborating with SA Harvest. The results speak for themselves: 67% pass rate in 2023, 78% in 2024 and a phenomenal 88% in 2025.

Salt River Secondary School’s NSC results:

Salt River Secondary School’s NSC results:

67% (2023) → 78% (2024) → 88.8% (2025).

When learners are fed, they can show up and succeed!

“We are jumping up and down,” says Margolite Williams. And then they did something that matters even more: they named the truth about what it takes. They credited their teachers, their principal (“the legend Donovan”), their volunteers and their donors. They spoke like people who understand that change is built by many hands. Salt River High is not “proof that food solves education.” Nothing that complex has one cause.

But it is powerful evidence of something South Africa can no longer afford to treat as optional: when learners are consistently supported, including through reliable food systems, outcomes can move.

Architects behind the work

Impact is never only the visible people in the photograph. Often, it is made possible by the “quiet architects”, the connectors, donors, advocates, the people who keep the background systems standing so the front line can keep going.

That is where volunteers like Margolite Williams fit in: not as the headline, but as part of the scaffolding that allows a school kitchen to keep producing dignity, day after day. When those behind-the-scenes relationships unlock food, logistics, and continuity, they are not “helping.” They are co-building. They are making learning possible in places where hunger would otherwise be the loudest voice in the room.

What we’re asking for in 2026

If we want the momentum of success to snowball, we have to stop treating school feeding as seasonal generosity and start treating it as learning infrastructure.

The impact of your support will be incalculable:

Salt River High gave us a picture of what’s possible. The numbers are the headline, but the real story is the conditions underneath them: leadership, community, consistency and learners who can finally show up to school with enough in their bodies to carry the work.

That is what SA Harvest is fighting for: not just meals moved, but futures kept open.

And what a privilege it is to witness change.